Cheap Money Chases Cheap Ideas

The last two decades fueled an explosion of B2B SaaS companies, killed true productivity, and destroyed vast amounts of wealth.

Perhaps the greatest misconception of the past twenty years is that we have been living in an age of rapid software innovation. The reality is that we are emerging from the Great Pseudo-Software Age: one defined by over-valued enterprise software companies that destroyed vast amounts wealth and left companies shackled to expensive and unproductive SaaS tools.

A generation of venture capitalists built their portfolios on metrics that prioritized growth over profitability and sustainability, while founders optimized their pitch decks to align with these incentives. Meanwhile, CTOs and CIOs merely oversaw sprawling third-party software portfolios, homogenizing company operations. Many employees advanced by specializing in niche roles tied to SaaS certifications.

Problem solvers were replaced by power users.

The SaaS industry has experienced a meteoric rise over the past two decades due to an unprecedented flood of cheap capital. This easy money, a consequence of the business cycle, has distorted the true value of software, leading to a proliferation of redundant products and inflated valuations. The SaaS boom wasn't driven by innovation or an unlocking of a new technoligical platform, rather by the opportunistic pursuit of fast capital that resulted in net value destruction.

In a 2024 speech, investor Thomas Laffont revealed that since 2020, venture-backed IPOs have collectively erased $225 billion in market capitalization while generating only $84 billion in value. That’s a net wealth destruction of $141 billion. The NASDAQ returned 122% during that period.

Venture Capital portfolios are now plagued by zombie startups and dying unicorns. Meanwhile, solopreneurs and small teams of ten or less are building native-AI products and services and generating hundreds of milliions of dollars in revenue.

AI isn’t enhancing the SaaS industry, it’s destroying it.

There are some technical reasons why the AI revolution didn’t begin until post 2019. But there is one fundamental reason: cheap money chases cheap ideas. This is why you didn’t see frontier AI labs in the early 2000s getting billions in funding to build state of the art AI architectures. Why would you when you could make billions creating derivitive SaaS products with fuzzy markup math?

AI couldn’t be taken seriously until value creation was taken seriously and tangible value is difficult to create when interest rates are near zero. When capital flows too freely market discipline disappears and founders and investors focus on the lowest hanging fruit when looking to create companies.

To understand this dynamic you need to understand the rise of SaaS software as a byproduct of the business cycle.

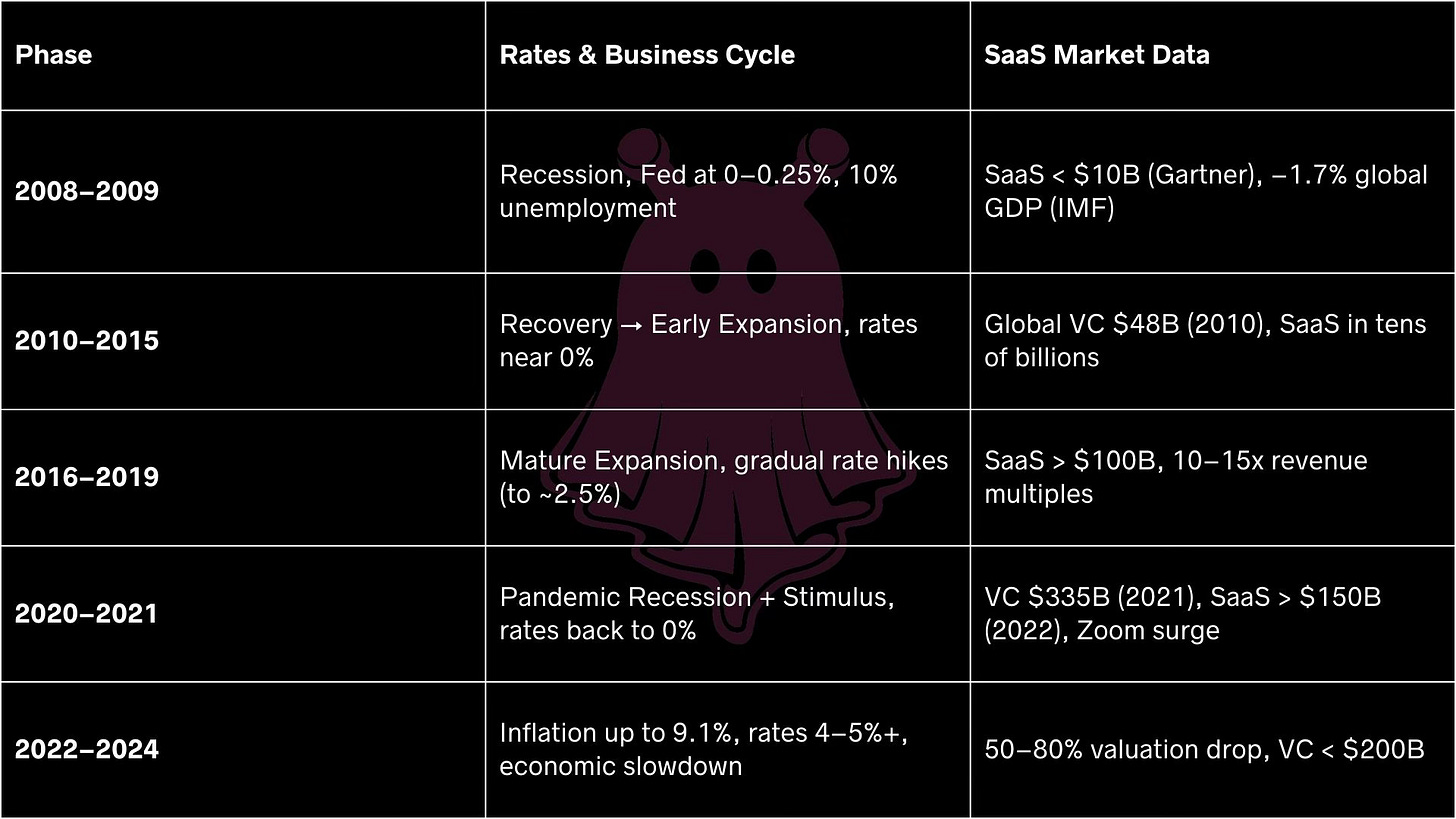

I. 2008–2009: Global Financial Crisis (Recession → Trough)

Between 2008 and 2009, the global financial meltdown triggered a severe recession, and the Federal Reserve’s effective funds rate fell below 0.25% in late 2008 (FRED). Unemployment in the United States reached 10% in October 2009 (BLS), and global GDP contracted by –1.7% in 2009 (IMF World Economic Outlook). At that time, the entire SaaS market generated less than $10 billion in annual revenue (Gartner estimate). Many early adopters began testing subscription models because they wanted to avoid large upfront license fees.

II. 2010–2015: Post-Crisis Recovery and Early Expansion

From 2010 to 2011, the economy moved through a recovery phase, then transitioned into an early expansion period from 2012 to 2015. During this span, interest rates remained at 0–0.25%, resulting in cheap credit that attracted venture capital (VC). The Fed Funds Rate averaged about 0.13% between 2010 and 2015 (FRED).

Global VC funding increased from $48 billion in 2010 to over $100 billion by 2015 (PitchBook). Investors became especially drawn to tech startups in the SaaS realm, placing a higher priority on rapid growth than on profitability.

A well-known anecdote from this era is Slack’s origin story. Slack was born from a failed gaming startup called Tiny Speck. Between 2013 and 2014, Slack raised significant rounds of funding and quickly reached a valuation above $1 billion, illustrating how cheap capital favored fast-growing B2B software tools. This period set the stage for widespread SaaS adoption as businesses recognized the benefits of pay-as-you-go solutions. Investors and founders continued to emphasize top-line growth, even when profits were small.

Did Slack really create something new and innovative? Or did it leverage cheap capital to recreate enterprise communication into a sleek UI, brute force network effects with that funding, mark up its valuation based on other startups, and sell at an inflated valuation of $27.7 billion to a predecessor that did the same? Did switching from email, texts, and instant messaging to email, texts, and Slack boost global productivity? Of course not. But it made a lot of people rich.

III. 2016–2019: Mature Expansion and Pre-Pandemic Plateau

From 2016 to 2019, economic expansion continued, and the Fed gradually raised rates to about 2.5% by 2019 (FRED). In the U.S., unemployment dropped below 4% in 2018 (BLS). During this time, VC investment rose from $120 billion in 2016 to nearly $280 billion by 2019 (PitchBook). Mega-rounds exceeding $100 million became common, enabling SaaS companies to secure multi-billion-dollar valuations.

Overall SaaS revenue surpassed $100 billion by 2019 (Gartner). Publicly traded SaaS firms were valued at crazy multiples. However, the swift ascent of certain companies also revealed systemic risks in the system.

Zenefits, an HR software startup founded in 2013, grew rapidly and at one point was valued at over $4.5 billion. However, in 2016, state regulators discovered that the company had allowed unlicensed employees to sell insurance, a clear breach of industry regulations. This led to a series of investigations, significant fines, and ultimately a major overhaul of its business practices. The scandal forced Zenefits to dismiss several top executives, including its CEO, and undertake a comprehensive restructuring to address its compliance failures. Zenefits' rapid growth and ambitious scaling contributed to a culture that emphasized speed over compliance, leading to a breakdown in internal controls and adherence to legal requirements. While the company continues to operate today, its valuation is most likely in the low $100M.

IV. 2020–2021: Pandemic, Rapid Recession, and Historic Stimulus

When the pandemic struck in 2020, GDP declined sharply in the second quarter (U.S. annualized real GDP fell –31.2%, according to the BEA), but rebounded quickly in the third quarter thanks to unprecedented stimulus. Unemployment briefly spiked to around 14.8% in April 2020 (BLS) before improving somewhat with partial economic reopenings.

Monetary policy shifted to another round of rate cuts as the Federal Reserve reduced rates back to 0% in March 2020. Meanwhile, fiscal authorities injected trillions of dollars into the U.S. economy through initiatives like the CARES Act. These measures helped push global VC funding to $335 billion in 2021 (PitchBook). With organizations pivoting to remote work, SaaS tools began popping up everywhere. Valuations for collaboration tools and digital transformation software soared.

By 2022, SaaS revenues exceeded a $150 billion annual run rate (Gartner). Zoom serves as a prominent example: it expanded from about 10 million daily users before the pandemic to 300 million by April 2020 (Zoom). Its market cap briefly topped $100 billion in 2020 (Nasdaq). Another major move was Salesforce’s acquisition of Slack for $27.7 billion, highlighting the peak in SaaS valuations during this period (maybe the best timed exit of the era).

V. 2022–2024: The Party Is Over

In 2022, inflation in the United States rose to 9.1% in June (BLS CPI), the highest level in decades. Central banks responded by aggressively raising rates to roughly 4–5% or higher in 2023–2024. This tightening of credit conditions created recessionary pressures in most industries.

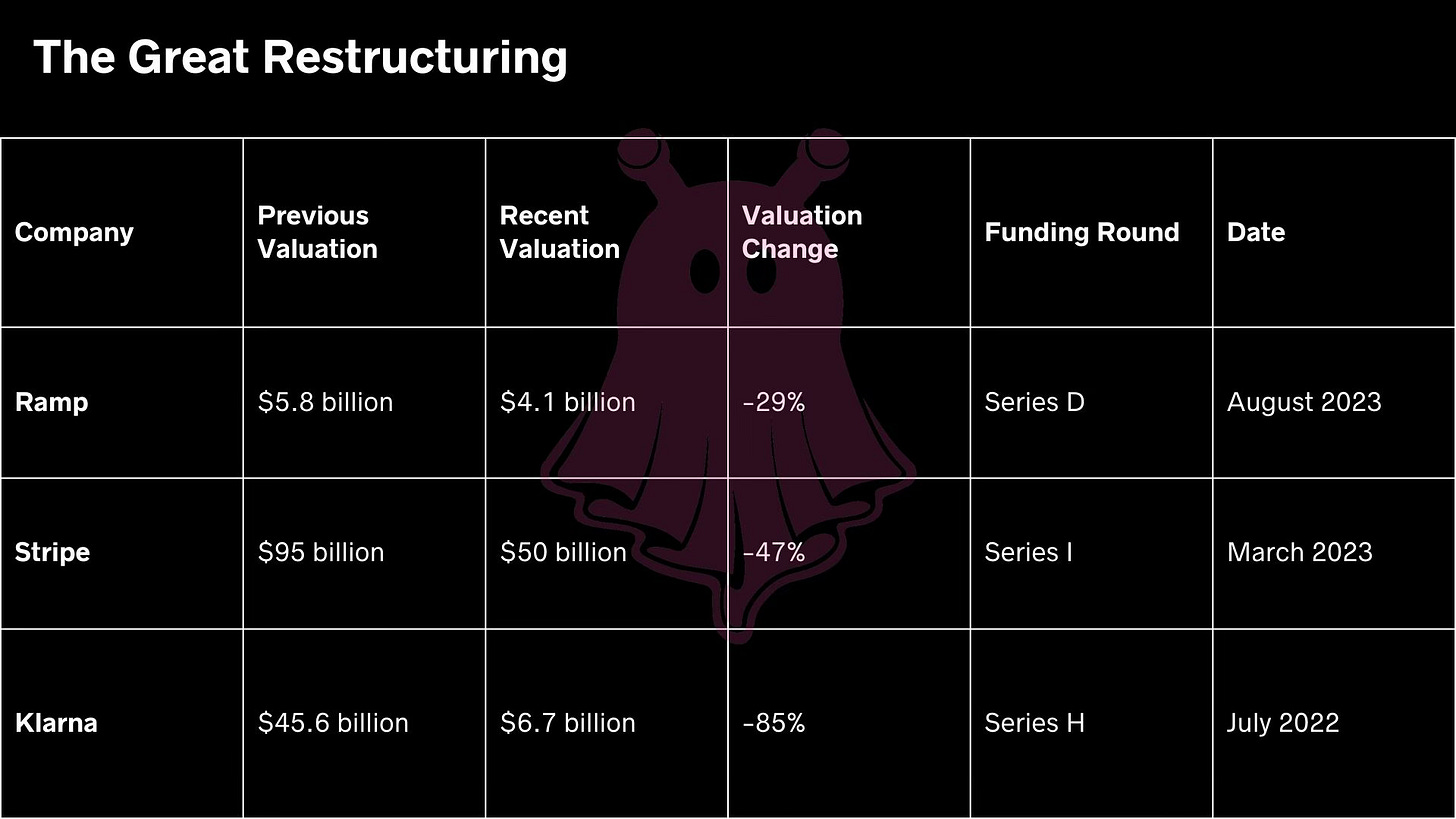

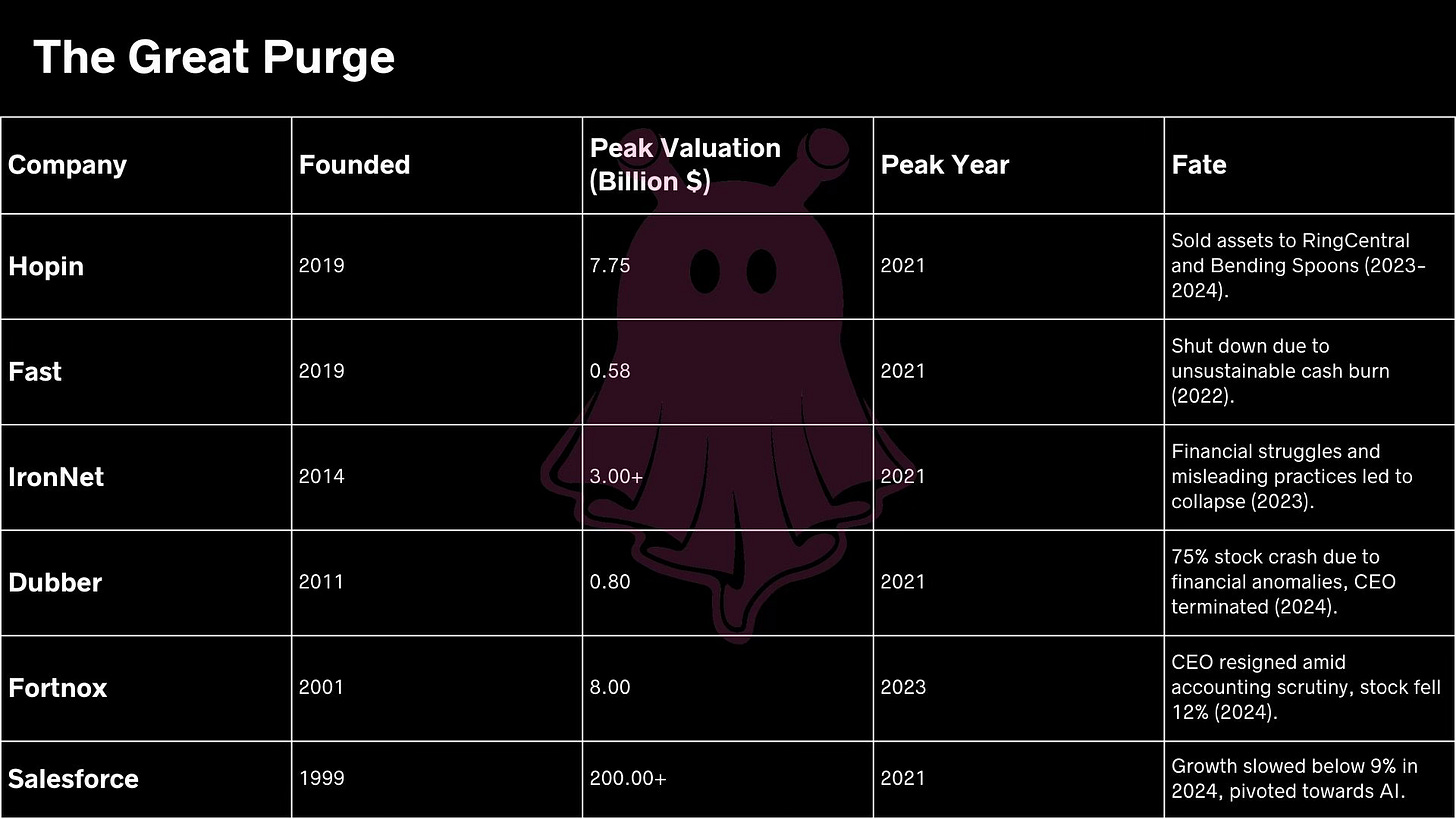

After a record high of $335 billion in VC funding in 2021, investment dropped below $200 billion by 2023 (PitchBook). Late-stage SaaS companies experienced significant down rounds. In the public markets, SaaS valuations fell by 50–80% compared to 2021 peaks. Firms that lacked profitability saw the sharpest declines, and layoffs became frequent at companies such as Salesforce, Zoom, and HubSpot.

A telling anecdote is Hopin, a virtual events platform founded in 2019 that reached a valuation of $7.75 billion just two years later. After this meteoric rise fueled by pandemic-era capital and demand, Hopin encountered unsustainable business conditions. By late 2022, the company initiated significant restructuring—including workforce reductions of nearly 30%—and by early 2023, its core operations were sold off to a strategic buyer, effectively dissolving Hopin as an independent entity.

Fast, true to its name, reached a peak valuation of $580 million just two years after its founding before it abruptly shut down in April 2022. The company only generated $600,000 in revenue at its peak while spending roughly $10 million per month. Despite raising $120 million in a Series B round led by Stripe (which took a $45 billion haircut in 2023), the math was never going to work in a world that was increasing the cost of capital.

Interest rates calibrate the barometer for innovation. Hopin and Fast are prime examples of low-hanging fruit companies joining the ZIRP party too late.

On the surface this looks like a typical market correction. But the ugly truth is most of these companies, like Hopin and Fast, should’ve never existed in the first place. This is most evident in the net wealth destruction these companies produced over this time period.

Moreover, most of this software intellectual property is now easily reproducible by AI at a fraction of the cost (by up to 75% by my estimates). While these applications may benefit from AI, the true power of AI is encumbered by them.

AI exposes a dark secret hidden in cap tables and balance sheets: software is worthless and no one knows how to value it.

In the Age of AI, you can no longer assume that producivity software increases producivity. Not when AI is deflating costs, margins, labor, and companies.

AI’s valuation model is diametrically opposed to the SaaS valuation model.

As AI models become more generalizable in their intelligence, the more of a commodity they become. At the same time, the sophistication of these models expands the surface area of their applicability, driving the cost of productivity down.

This means that the cost of productivity will fall to a nominal price above the energy cost to complete the task. Traditional software, even if it is emmbedded with AI, cannot survive in that valuation model. Additionally, traditional software logic remains a barrier to the pure transfer of energy to productivity.

So what is Artificial Intelligence, really? There are many definitions. But only one really matters…

AI is the transfer of energy to productivity by automated means.

As we drive the price of software down to zero with AI, the true value of workflow automation will be derived from it's energy transfer efficiencies.

The more energy we can transfer to productivity, the more value we can create.

This is the formula for true productivity. This is the formula to boost GDP growth from a flatlined 2% to sustained growth above inflation. For this formula to hold true you cannot have hundreds of niche software silos largely doing the same thing, with employees trained like monkeys pointing and clicking through complex business logic.

So how do we build a system to achieve the purest form of energy transfer to productivity?

Enable transaprent price discovery: Artificial intelligence has no problem pricing itself. When energy usage, compute, and memory are the primary costs, you can measure productivity by direct inputs—kilowatt-hours and cycles—not by contrived and opaque metrics (MAU, LTV:CAC, etc.). By contrast, legacy SaaS contracts still rely on complicated, user-based or seat-based pricing that obscures the true cost of delivering productivity.

True price discovery means eliminating the noise of “value-based pricing” or “premium features” in favor of simple, usage-based economics. AI, by its very nature, demands it. As models become more sophisticated and general, their underlying compute-and-memory load is the only real pricing signal. Over time, the market will select for services that convert energy into productivity more efficiently.

Invest in the bottlenecks: If AI is ultimately about energy conversion, it follows that our biggest constraints are energy production and the hardware that harnesses it. As the cost of capital sustains a price above 4%, only those technologies that directly reduce operational overhead and time-to-productivity will survive.

Divest in legacy SaaS: Legacy SaaS platforms, built for a low-interest, infinite-growth era, are now misaligned with a world where energy and compute drive value, leading to diminishing returns on productivity. AI-based automation will replace many of these bloated tools, offering equivalent or superior functionality at a fraction of the cost, making systematic SaaS contract reductions essential for freeing capital to invest in real growth levers like hardware and advanced automation. As AI automates routine workflows, businesses must realign skills toward creativity and problem-solving, or risk obsolescence in a landscape where AI-employee interaction directly impacts the bottom line.

Cheap money gave us the Great Pseudo-Software Age—a time defined by easy capital, derivative startups, and valuations untethered from reality. When profitability finally mattered again, the bubble burst. AI is not here to prop up these vestiges of the old guard. It’s here to supplant them entirely.

Every AI model at its core is a self-orgnizing software system that transforms data and compute into actionable outputs. The more efficiently it does so, the more value it creates. If software once existed to digitize repetitive workflows, AI now eliminates the drudgery altogether—and most of the overhead it required.

The productivity gains from AI hinge on a straightforward principle: energy in, productivity out. Those that generate real value in this new era will focus on refining that process to its purest form.

The winners in this new epoch are those who recognize that AI is not a sub-feature of software, it’s an entirely new paradigm of software and opportunity to create real value.

I’ll close with this. There is an obvious and self-induced debate on AI- it’s value, it’s hype, it’s danger. We engage these debates like there is some deterministic end state that we are betting on. But these arguments are just prisms into the various psyches and worldviews of those in that debate at that present time. The future is not a real thing. It is simply the arrival of our collective actions. And the present is simply the management of those actions, now passed.

We should rebuild processes around AI as a direct channel from human intent to value generation. The Age of AI is an opportunity to build a Second Industrial Revolution. This means removing layers of complexity that inflate costs. It also means accepting that the Great Pseudo-Sofware Age was a detour. AI is a new technology platform and not a byproduct of a business cycle that generated cheap ideas.