AI’s Cambrian Explosion For Enterprise Creativity

AI is not merely a feature added onto software, it is fundamentally changing what software is.

In the heart of Cambrian Forest, the Weaverbirds wove their nests as they always had, crafting homes that bore the wisdom of generations. Elara, a master weaver, was known for her precision. Her work was a symbol of the canopy’s progress.

One season, she discovered a strange egg in her nest—larger and darker than her own, its surface shimmering like stone polished by invisible hands. The forest whispered uneasily of such eggs appearing in nests across the canopy. Yet Elara, proud of her craft, chose to keep it. “If my nest can hold this,” she thought, “then let it be.”

When the egg hatched, Elara was struck by the bird’s figure: iron-like wings, deep green eyes, a silver tongue, and porcelain beak. It looked nohting like a Weaverbird. Yet, Elara felt an uncanny resemblance. She named it Koo.

While her other chicks stumbled, Koo moved with remarkable precision. It watched Elara weave, then crafted threads tighter, stronger, and faster than hers in mere minutes. It found food where none had been before and devised new weaving techniques.

Birds across the canopy mimicked Koo’s techniques, and soon nests stretched across every branch—larger, more intricate, brimming with new life. The forest began to change. The canopy teemed with activity, nests reaching higher, stronger, into spaces once thought unreachable.

But harmony gave way to strain. The trees groaned under the weight of so many nests, their branches splitting. Resources dwindled as birds competed for materials, and smaller nests were overshadowed or pushed aside. Some Weaverbirds were pushed out of their nests.

Elara watched as her world transformed into something both awe-inspiring and unsettling. Her heart swelled with pride at what Koo had unlocked, but it also ached for what had been lost. The canopy was no longer a ecosystem of growth.

One morning, she awoke to find her nest empty. Koo had taken flight. High above the canopy, it soared, its metallic wings reflecting the sunlight.

“Koo!” she called.

Koo turned in midair, expressionless. A face that read- this is what you taught me…this is all I’m made to do.

Koo returned his eyes to the sky.

Weaverbirds paused, watching Koo disappear. Slowly, they began to take flight one-by-one, leaving behind the Cambrian Forest to explore the open sky.

Elara sat alone in her empty nest. She began to weave again, not as she once had, but differently. Her threads were lighter, her patterns more open, as if leaving space for something unknown. Elara was no longer a keeper of tradition. She was a witness to evolution, and it flew away to create something new.

This is Part III of Revenant Research’s top themes of AI for 2025.

Introduction

Enterprise software has evolved through five major phases shaped by hardware evolution. It began with highly bespoke, expensive applications on mainframes (Phase I), where only large organizations could afford the teams and infrastructure required to tailor COBOL or Fortran code to their exact workflows. As smaller, cheaper machines emerged, standardized off-the-shelf software (Phase II) allowed companies to license and install solutions more quickly. The advent of the internet and web applications brought about the explosion of B2B SaaS (Phase III), lowering hardware overhead but causing new issues with escalating subscription fees, vendor lock-in, and forced, one-size-fits-all workflows that often clashed with organizational practices. These hidden downsides became clearer when enterprises realized they were juggling overlapping tools and paying for unnecessary features while struggling to align their processes to third-party software.

Now, a new phase (Phase V) is emerging through Native AI software, where small teams equipped with AI Agents and coding tools can build and refine custom applications 75% cheaper and faster than legacy B2B SaaS. This phase has the promise to restore enterprise software to its original purpose.

Phase I: Custom Software on Big Dumb Machines

Enterprises in the 1960s and 1970s invested millions of dollars in mainframes from IBM and UNIVAC, installing them in climate-controlled rooms with raised floors and reinforced supports to handle large, spinning disk units. Electrical wiring had to be upgraded for high amperage, and cooling systems ran continuously to maintain stable temperatures. Memory ranged from only a few dozen kilobytes to a few hundred, so developers wrote tightly optimized programs in COBOL or Fortran. They used Job Control Language (JCL) scripts to queue batch jobs for payroll, record-keeping, and other core functions. If one control card was misplaced, operators had to halt the entire run and re-sort the deck, a tedious process that wasted critical machine time.

Much of the software was built from scratch because vendor-supplied libraries were limited, and few commercial packages existed. Specialized staff handled memory overlays, managed tape drives, and monitored the machines as they processed thousands of transactions. Given the high cost of both hardware and engineering labor, only large institutions could afford these systems, yet they gained significant efficiency by automating tasks that previously required entire clerical teams. Over time, the complexity and expense of mainframes entrenched their role in IT departments, defining enterprise computing for decades to come.

Phase II: Standardized Software on Desktops

By the 1990s, the introduction of personal computers shifted the enterprise computing landscape. Systems like the DEC VAX, the Macintosh, and IBM’s PC line ran on operating systems such as DOS, Windows, and various UNIX flavors. Because these machines were less expensive and required fewer specialized facilities than mainframes, organizations adopted them more widely. Software vendors began shipping standardized applications on media such as tape cartridges, floppy disks, and then CD-ROMs, allowing companies to purchase enterprise software suites rather than building everything from scratch.

During this period, the client-server model gained traction. Tasks like data processing and complex queries moved to a dedicated back-end server, while each user’s desktop handled the interface. This setup let businesses add more servers or PCs incrementally, rather than overcommitting to a single, large computer. Companies like Oracle, Microsoft, SAP, PeopleSoft, and Siebel offered applications designed for repeatable deployments, contrasting with the bespoke solutions that mainframes required.

Enterprises saw faster installations and lower costs than in the mainframe era. Still, many found that standard applications needed significant configuration or “semi-custom” adaptation to fit existing processes or integrate with other systems. Licensing deals frequently came with substantial one-time fees plus annual maintenance costs that climbed as user counts grew. Version upgrades, patch management, and the challenges of managing hundreds or even thousands of desktops added complexity, leaving organizations with new hurdles even as they benefited from a more flexible, distributed model.

Phase III: The B2B SaaS Explosion

During the early 2000s, organizations began taking advantage of the internet and maturing web technologies to centralize data and processing in hosted environments, accessible through a browser. This model evolved into Software-as-a-Service (SaaS), where vendors maintained a single codebase serving many customers at once. Salesforce pioneered a multi-tenant architecture that allowed updates to roll out instantly to all tenants without requiring separate installations. Vendors charged periodic subscription fees covering software usage, hosting, support, and upgrades, converting what had been capital expenditures (hardware and perpetual licenses) into an operational, pay-as-you-grow model.

A wide range of SaaS offerings soon appeared—covering HR, marketing automation, analytics, customer service, data warehousing, and more. Cloud providers like Amazon Web Services (commercially launched in 2006) and Microsoft Azure (2010) provided on-demand compute, storage, and networking, slashing upfront costs for SaaS startups. As more vertical solutions emerged, enterprises increasingly chose to subscribe rather than build, attracted by quick deployments and frequent feature updates. This approach led many large organizations to license dozens—or even hundreds—of SaaS applications, dramatically expanding their software portfolios.

Once SaaS vendors reached a critical mass of customers, they often operated at 60–80% profit margins, even though their annual overhead—salaries, hosting, development—could run into tens of millions of dollars. At scale, each new customer added little to overall costs, boosting margins and drawing investor attention. This confluence of multi-tenant efficiency, recurring subscription revenue, and on-demand cloud infrastructure defined a new era of enterprise software.

Phase IV: SaaS Gluttony and the Death of Innovation

The SaaS explosion inevitably created unintended consequences. While each individual solution appeared cost-effective at first, a company using dozens, even hundreds, of SaaS applications ended up paying subscription fees month after month, year after year, often only utilizing a fraction of the features. As the SaaS platforms grew, the business logic standardized. Thousands of companies were forced to operate the same way, recieve the same training, and even develop specific roles to become subject matter experts and adminstrators of third-party software. Even then, custom integration had to be developed to connect the disparate third-party software subscriptions together via APIs.

As more departments within an organization licensed specialized SaaS platforms, fees added up. Compounding the problem was the fact that many of these services were designed as one-size-fits-all solutions. Vendors tried to accommodate multiple industries and use cases in a single product, necessitating a standardized approach to operations,effectively eliminating the ability to innovate and develop mroe efficient workflows aling to business objectives. Enterprises had to reorganize their internal processes or training programs around the vendor’s structure, generating additional hidden costs in the form of operational alignment, data migration, and change management.

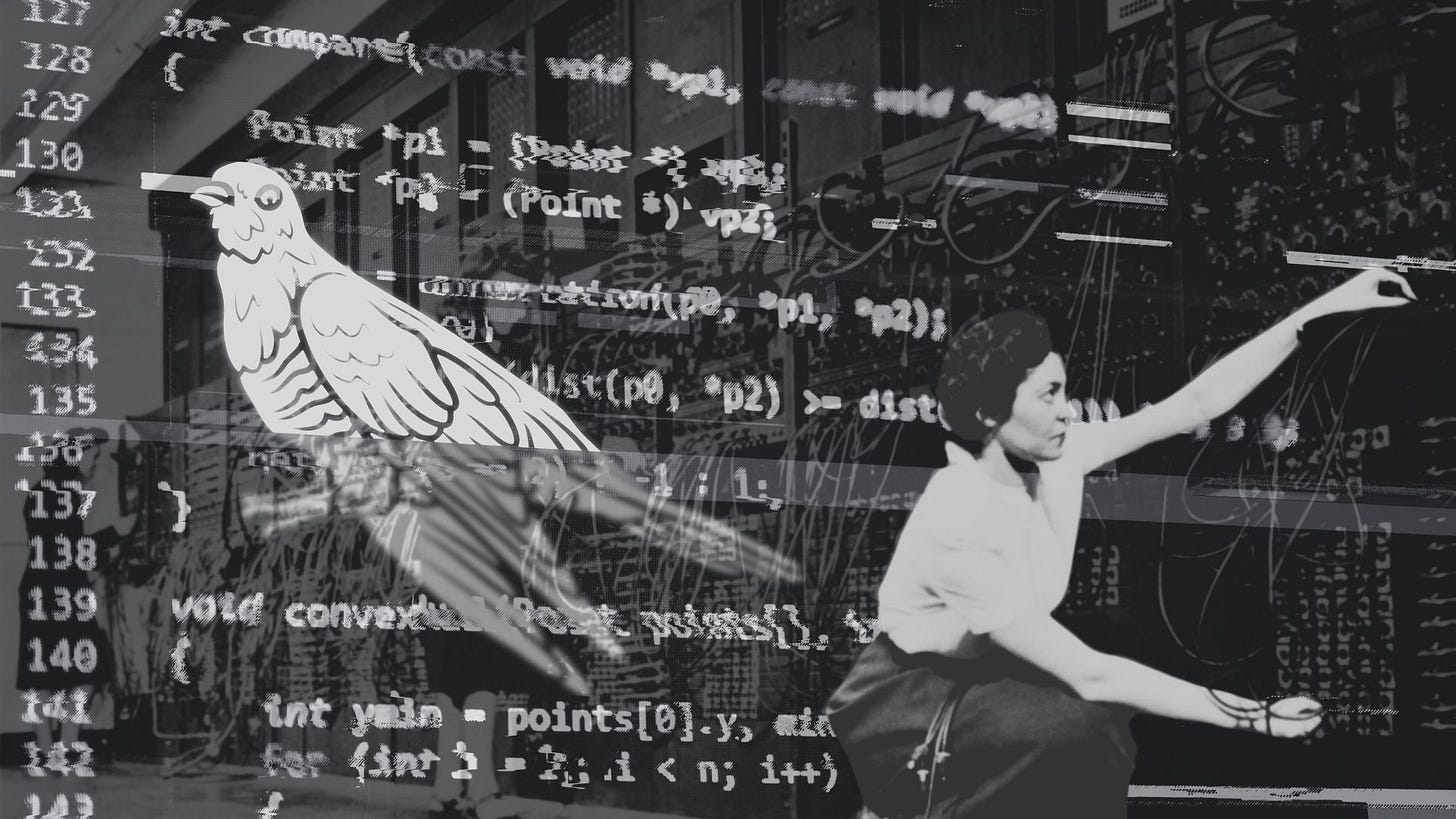

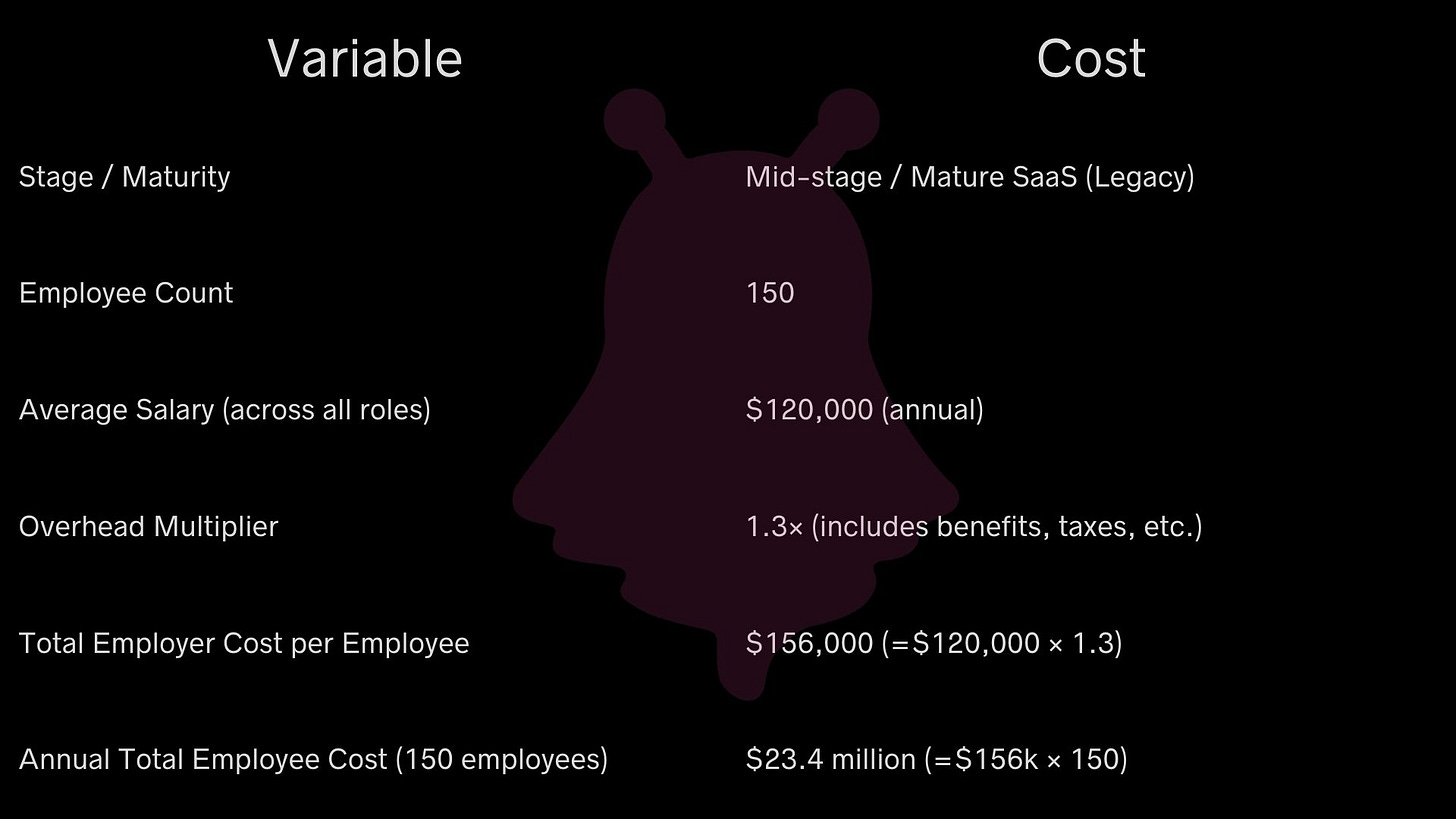

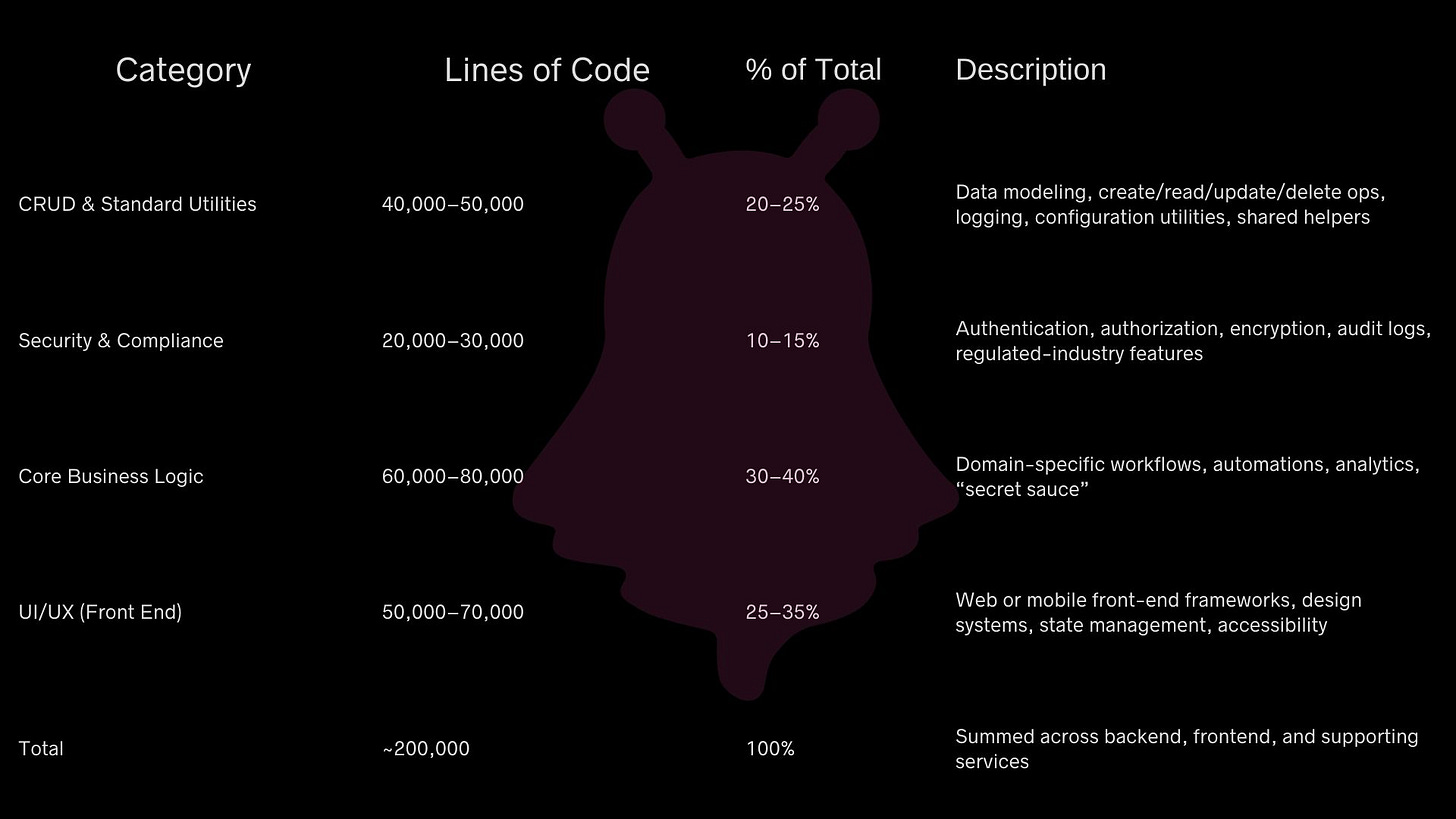

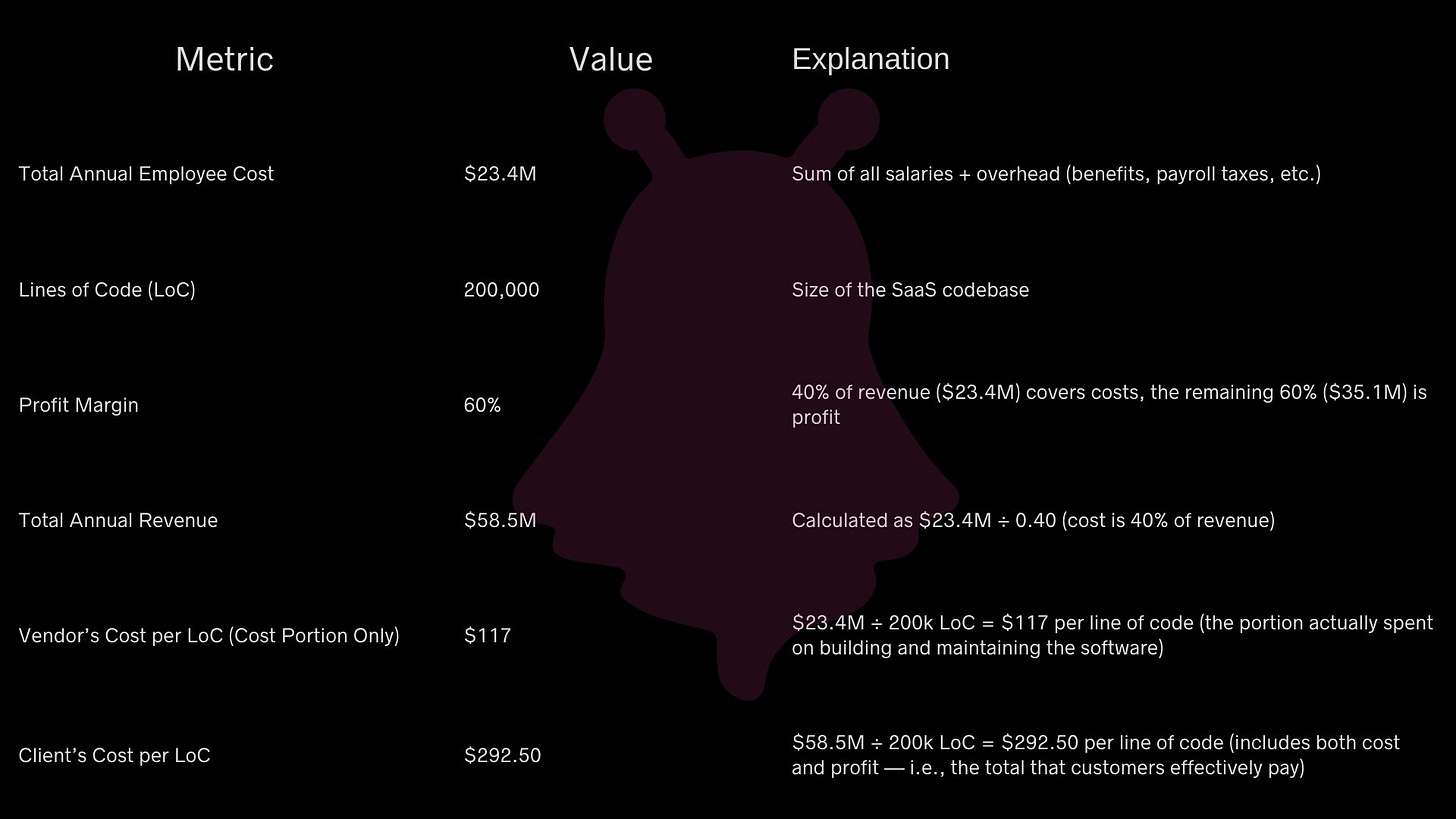

To break it down the true cost of SaaS subscriptions: a mature B2B SaaS offering might have a codebase of 200,000 lines. The vendor’s direct spend on building and maintaining that code would the total approximately $23.4 million annually, equating to $117 per line of code. Once a 60% profit margin is added, the cost to the customer effectively becomes around $292.50 per line of code. Businesses are thus paying not only for the engineering effort, but also for features they may not fully need, plus the overhead to market and sell the product to other customers. Every company is operating the same way and subsidizing each other’s operations.

Total Cost of B2B SaaS Software:

Breakdown of B2B Codebase:

Total Cost Per Line of Code:

In the face of escalating subscription fees and over-standardized workflows, native-AI software introduces another major shift in enterprise computing. With AI coding tools teams can drastically reduce the development overhead for tasks that previously required scores of engineers. LLMs and AI Agents can orchestrate workflows via natural language, retrieve context from specialized knowledge bases, and even handle dynamic integration with third-party services, cutting down on the lines of code that must be manually maintained.

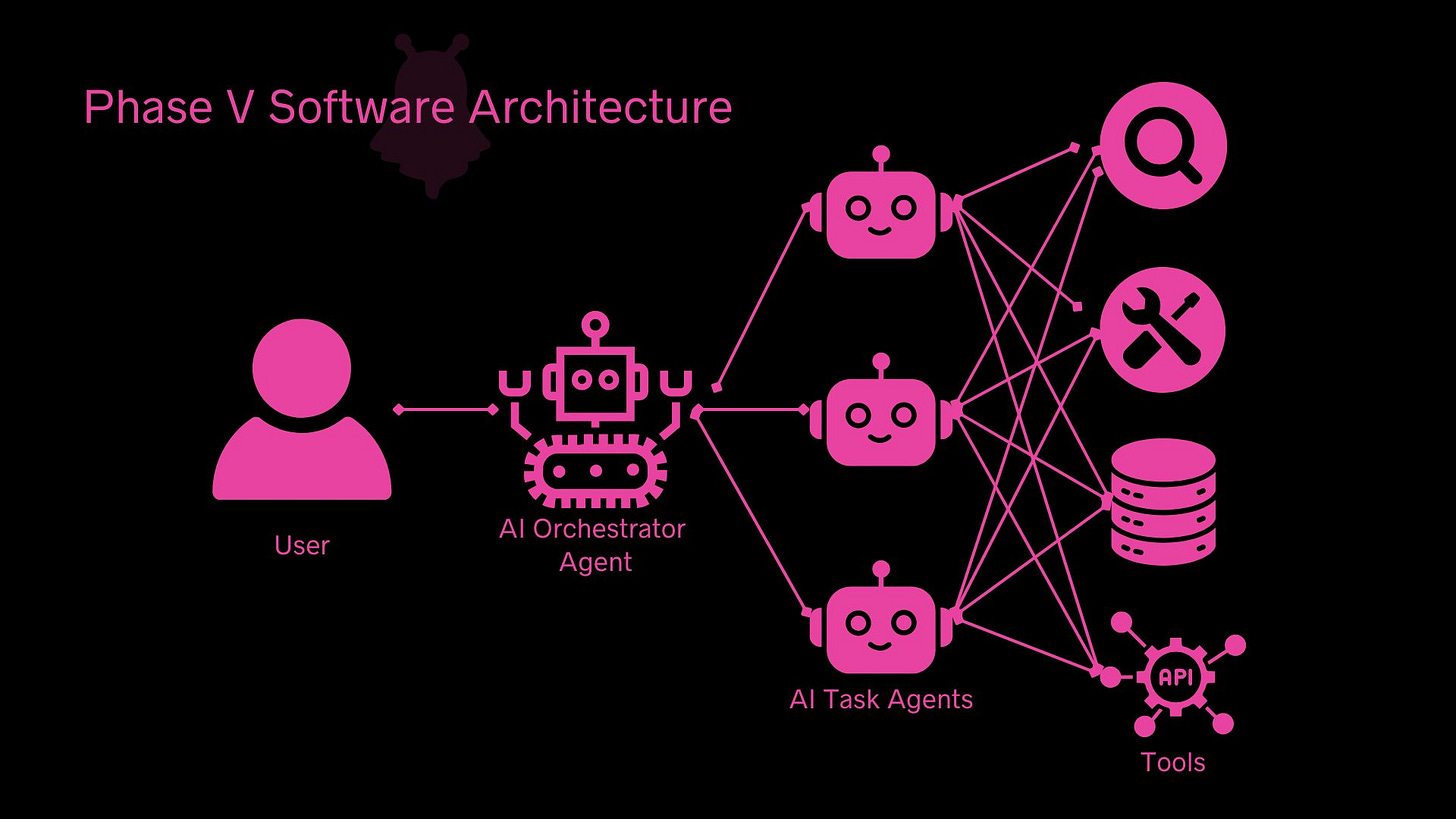

AI plays two key roles in Phase V software architecture. First, AI coding agents and tools work for software engineers to generate utility, security, and compliance code at near zero marginal cost. This 60% of the code base is standardized with well defined requirements. The second role AI plays is in replacing the traditional core business logic layer of software architecture. AI orchestrator agents and domain specific AI agents work together to search the web, query databases, call tools and algorithms, and APIs to dynamically sequence business logic from the user’s instructions.

This is how Revenant Research builds software. Sensitive and critical functions are coded into tools. Client data is stored in vector databases so agents can tailor results to the client, and external access is integrated via web search and APIs. Auditing and governance guardrails are baked into the orchestration. The AI Orchestration layer handles the coordination of tasks. User’s can save routine tasks as one click workflows and even schedule them to perform autonomously.

In the native-AI scenario, around 80% of code is generated and replaced by AI. Software engineers don’t need to design, architect, and code all of the specific workflows. Users don’t need to be trained to navigate complex, hard-coded sequences. With native AI applications, an AI layer orchestrates workflows dynamically based on the user’s directions. The AI orchestration layer interprets the user’s request and dynamically sequences a workflow. Instead of being locked in rigid codified workflows, the AI agent learns and performs better as it learns from the dynamism of user instructions.

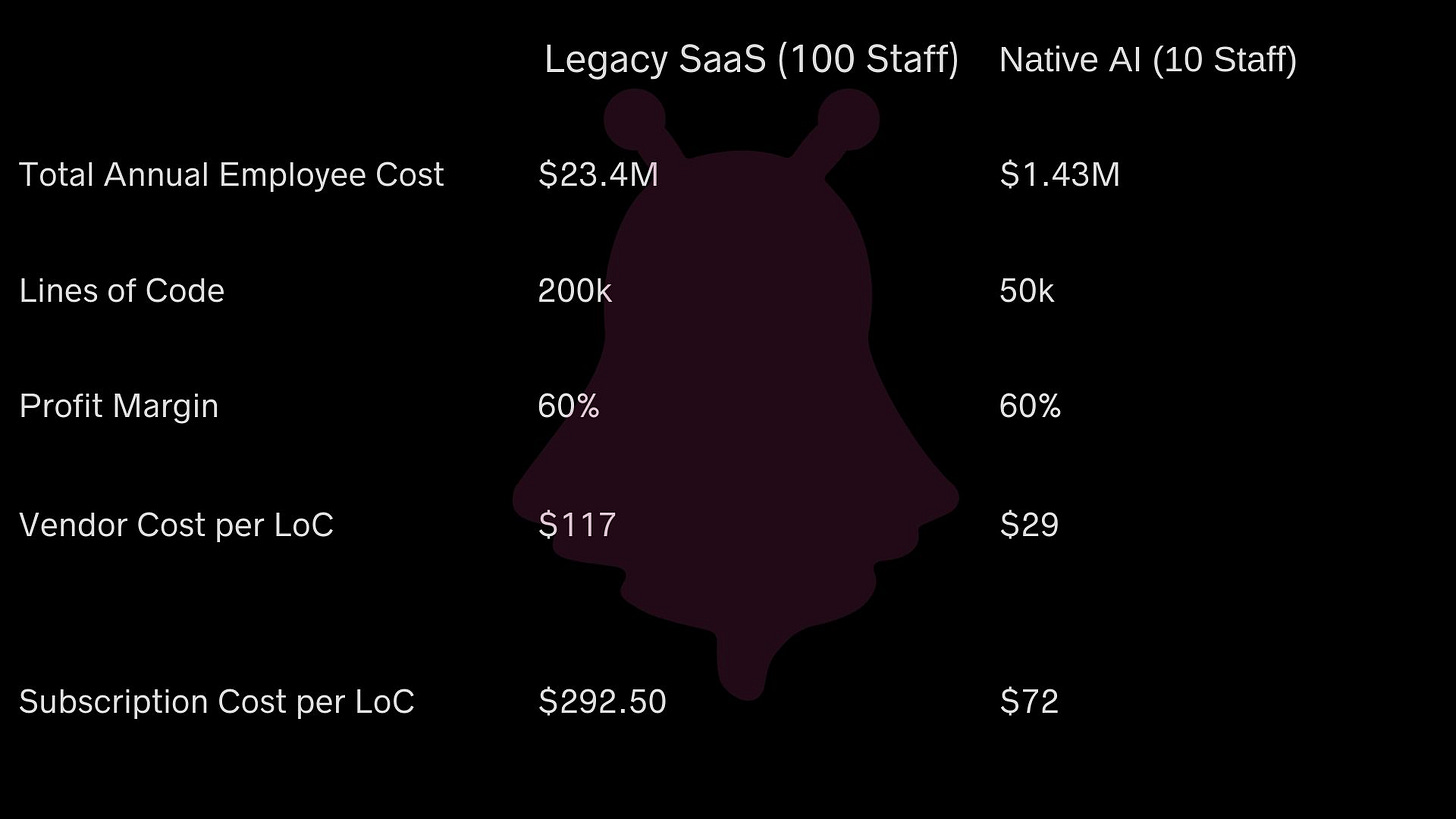

As a result, the vendor’s cost per line of code falls from $117 in the legacy SaaS environment to just $29 in a native-AI software architecture. That transaltes into a 75% reduction in price for the customer, even if the software provider retained a 60% profit margin.

AI’s Cambrian Explosion of Enterprise Creativity

Phase V represents not just an evolution in enterprise software but a reimagining of its purpose. By leveraging the dynamic capabilities of native-AI, businesses are empowered to move beyond the limitations of rigid, standardized workflows and rediscover the agility of creative problem solving.

Yet this transformation is not without its complexities. Like the Cambrian Forest, the adoption of native-AI will reshape the landscape. Some organizations will adapt quickly, embracing the flexibility and creativity unlocked by native-AI. These pioneers will build applications that evolve in real-time, tailored to their unique processes, enabling new heights of innovation and growth. Others, accustomed to the structure of legacy systems, may struggle to relinquish the familiar, choosing instead to refine and maintain what they already know.

Not every business will soar, or even survive. But those that do will explore untapped opportunities, charting paths toward a future unbounded by the constraints of traditional software. Imagine the competition and subsequent innovation when companies are unleashed from operating the same way and subsidizing each other.

Ultimately, the power of this phase lies in its ability to restore the creative agency that enterprises lost in the era of one-size-fits-all SaaS solutions. It is not merely a technological shift but a cultural one, requiring leaders to foster environments of experimentation and adaptability. The most successful organizations will not only embrace the tools of the future but cultivate a mindset ready to explore the vast potential of the horizon.

It’s time to leave the canopy.